The Taste of Memory

From pumpkin spice to apple pie, flavors bring back more than taste. Consider how memory and feeling intertwine.

Key Takeaways:

- Declarative memory stores facts and figures, while taste memory is non-declarative, harder to articulate but deeply felt.

- Taste is processed in gustatory cortex within the insula, with neurons specialized for sweet, bitter, and other flavors.

- Associative taste learning protects survival—we avoid foods linked with illness through hippocampus–gustatory cortex interaction.

- Pleasant taste memories activate the brain’s reward centers, tying flavors to joy, comfort, and positive emotional recall.

- Taste memory is fundamentally emotional, transporting us to specific times and feelings more vividly than declarative memory.

When psychologists study human memory, they tend to focus on the kinds of memories you formed when you did schoolwork – remembering facts or numbers. This is called declarative memory, because you can explicitly declare what it is you’re remembering. Remembering who was president in 2012, or in 1812, or how many planets are in the solar system are declarative memories, because it’s information stored in your brain that you can just spit out and put into somebody else’s brain. But we have other types of memory that are significant—it's just that they are much harder to articulate (and therefore harder for psychologists to study). The memory of taste is one example of a non-declarative memory.

Think of the last nice meal you had at a restaurant. But don’t think of a list of foods that you ate, remember what some of those foods tasted like. The creaminess of a white sauce on pasta and the bite of the fresh-ground pepper. You can almost taste it, even though there’s no food on your tongue. It turns out that taste memories are coded in your brain in a very different way from other memories. Learning more about this process can help us understand something about how emotion impacts our senses.

Usually, when you make a memory, the information is coded into a region of your brain called the hippocampus. Call this the central memory hub in your brain. We know the hippocampus is necessary for memory because of some famous patients that had their hippocampi (you have one on each side of your brain) removed.1 Such patients are left essentially stranded in the past, unable to form new memories.

Image courtesy Art Institute of Chicago.

After a while, hippocampus memory is transferred to the largest part of your brain, the cerebral cortex. Honestly, scientists have no idea why or how your brain shuffles the memory into another part of your brain, some guess it’s to make “room” in your hippocampus for new memories2 - but nonetheless we’re pretty sure that your brain does this.

Taste memories, however, work a bit differently. When you drank your first ever pumpkin spice latte, the taste receptors in your mouth sent a signal through your cranial nerves to a specialized area in your brain called gustatory cortex, or taste cortex. Gustatory cortex is part of an odd area in your brain called the insula, which seems to be a kind of hub connected to a huge number of other brain regions. There are neurons in gustatory cortex that only fire when you taste something sweet (whether it’s birthday cake or a guava), other kinds of neurons that only fire when you taste any kind of bitter food, and so on.3

Actually, there’s a sort of division of labor going on here. While gustatory cortex is encoding the taste of your pumpkin spice latte, the hippocampus is encoding the fact that you drank it in a cafe with green furniture in Boston on a Thursday. Subjective flavors are processed in one area, and a totally separate area processes the what/where/when information.

But this is neuroscience – nothing is ever as simple as “this brain area does X, that other brain area does Y.” While gustatory cortex encoding and hippocampus encoding cover most foods you taste, others are extremely important for us on a basic biological level. Have you ever had food poisoning, and even after you’re better you’re still completely disgusted by whatever dish it was that made you sick? This is called associative taste learning, it’s a built-in survival mechanism that you and most of your fellow animals have so that you learn to be disgusted by (and therefore, avoid) things that you shouldn’t be eating.

In this kind of memory, in which you’ve learned to be disgusted by a taste because you associate it with illness, there’s crosstalk between the encoding of subjective taste in gustatory cortex and the encoding of what/where/when information in the hippocampus. A group of scientists in Israel and Japan conducted a study in which they gave mice a sweet taste (saccharin) with or without a drug that will make them feel sick.4 To learn about how the hippocampus might process taste, they used a genetic trick to keep the hippocampus from forming memories. They found that inactivating the hippocampus didn’t prevent mice from remembering the sweet taste – unless the saccharin was combined with the drug that made them feel sick. The mice only showed aversion to the sweet taste when their hippocampus was able to communicate with gustatory cortex. When certain tastes carry information important for your health or survival, your brain will engage a larger network of areas to remember those tastes.

Image courtesy Art Institute of Chicago.

Taste memory has another interesting property that declarative memories don’t: a strange ability to evoke deeply positive emotions, and transport us back to an important time of our lives. Remember the taste of a dish your family used to eat over holidays. It brings back warm feelings in a way that declarative memories just can’t. The reason is that your brain doesn’t only recruit a wide network when coding memories of tastes that make you sick, it recruits a wide network for any emotionally important taste. Besides gustatory cortex, pleasant tastes are also encoded in your brain’s reward centers.5 These are the deep structures in the middle of your brain that are activated by tasty food, sex, music that you love, or anything else you find deeply gratifying. When you remember the taste of apple pie at Thanksgiving, these reward pathways are reactivated along with gustatory cortex, and this is why the taste memory elicits positive emotions.

Remembering taste is not an analytical process, in which sterile sensory information is stored for later use. It’s a fundamentally emotional process, inseparable from our built-in subjectivity.

References

1 Rose, Steven. “Patient HM Review – a Botched Lobotomy That Changed Science.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 25 Aug. 2016.

2 Gravitz, Lauren. “The Forgotten Part of Memory.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 24 July 2019, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-02211-5.

3 de Araujo & Simon (2009). "The gustatory cortex and multisensory integration." Int. J. Obes, 33:S34-43.

4 Chinnakkaruppan et al. (2004). "Differential contribution of hippocampal subfields to components of associative taste learning." The Journal of Neuroscience, 34(33):11007-11015.

5 Avery et al. (2020). "Taste quality representation in the human brain." The Journal of Neuroscience, 40(5):1042-1052.

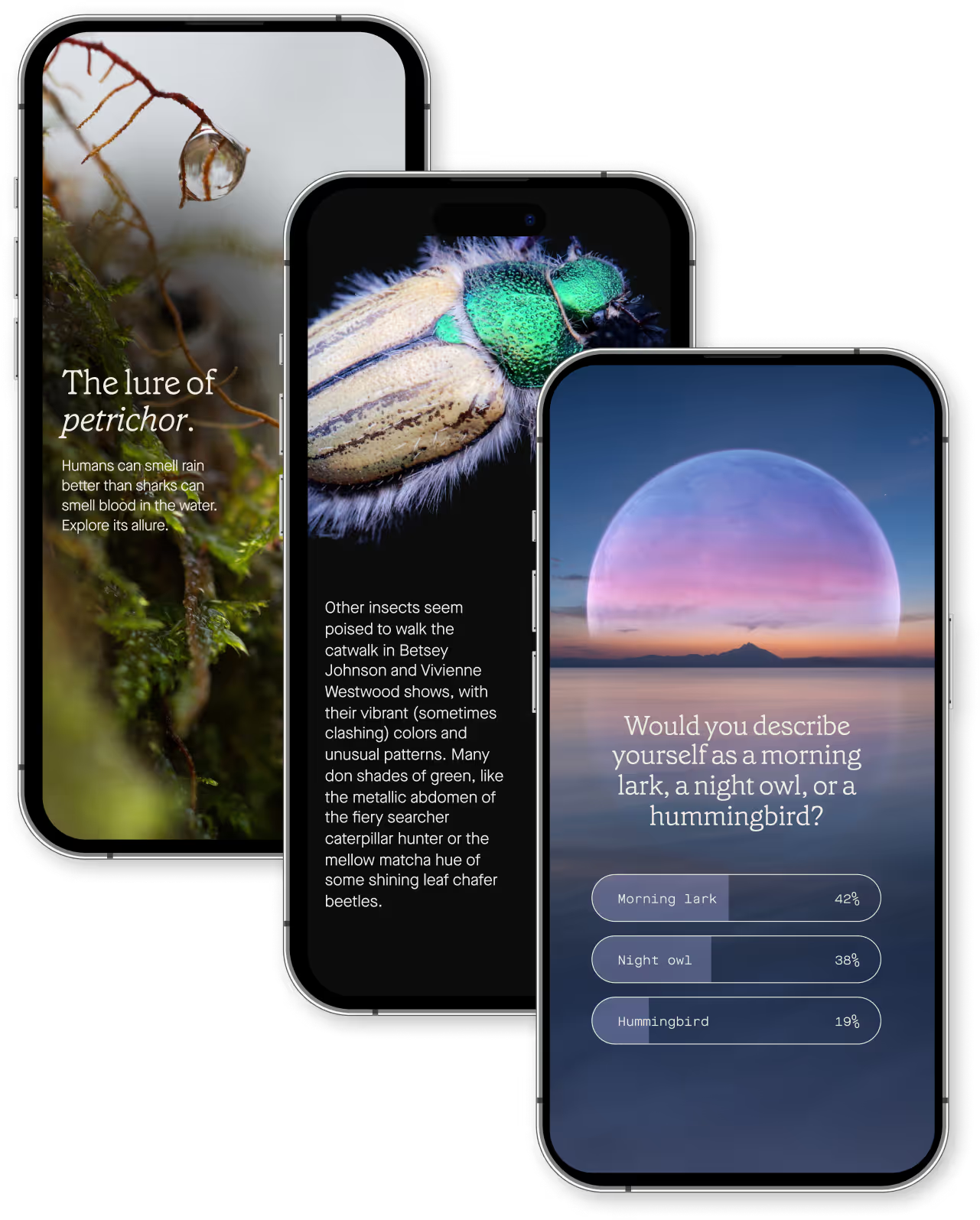

Build your practice of daily discovery.

7 days free.

Sign up for more bites of curiosity in your inbox.

Ongoing discoveries, reflections, and app updates. Thoughtful ways to grow with us.

.svg)