The Perception of Time: Part II

Why does time fly as we age? Memory and novelty may hold the key. Reflect on how you experience it.

Key Takeaways:

- Time perception differs from physical time—it can feel faster in joy and slower in fear.

- Flow states create the feeling that time flies, as focus and immersion block awareness of passing moments.

- Fear doesn’t literally slow time, but frightening events feel longer in retrospect because memory encodes them more deeply.

- Aging makes time seem faster since fewer novel experiences are encoded as lasting memories.

- Collective shifts in time perception occurred during the pandemic, with stress making time drag and calm making it fly.

In Part I we learned about the physics of time – why time is a one-way march from past to future and could never move backwards. The physics of time is always a mind-bending subject, and that’s because our minds just weren’t built to think about time the way physicists do. Time is an objective quantity of the universe, passing at a steady rate. But we’re humans – objectivity is not our strong suit. Our perception of time is anything but a neutral counting of the seconds passed.

Time can “fly” (seem to go faster) or “drag” (seem to go slower). When we’re experiencing positive emotions, time subjectively seems to pass more quickly.1 Whether it’s a mirthful night spending time with friends or an evening spent delving into a meal we love—enjoyment itself seems to make us feel like time is moving faster—this is the psychology of flow. Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi coined the term “flow” to describe being so joyfully immersed in something that everything else is shut out, feeling like time flies.2 A jazz musician improvising or a writer banging out a whole chapter in a flash of inspiration would be canonical examples of flow states. But flow doesn’t require some special creative talent; anyone can achieve this time-flying state with enough focused pursuit of something they love.

We’ve all heard that time seems to slow down during scary events, so-called time dilation—but do we actually perceive time differently when afraid? Psychologists at Baylor aimed to study time relativity and took test subjects to an amusement park ride in which you jump off a fifteen-story platform into a circus net (yes, these exist).3 The psychologists attached a screen to the test subjects’ wrists. These screens were flashing numbers, but too quickly for the subjects to actually read them. The test subjects’ job was to watch the screen during the fall. The idea is that if our perception of time slows down in moments of fear, then, when falling, the subject actually would be able to read the quickly-flashing numbers. It was a clever way to test the idea of time dilation—but it turned out that subjects weren’t any better at reading the numbers while falling than they were while on the ground.4 So it seems time wasn’t actually moving more slowly for people who were afraid.

Interestingly, when asked, the test subjects said they felt the experiment lasted longer than it did. They fell for about two and a half seconds, but they guessed it was closer to four seconds. This argues not that you perceive time more slowly during scary events, but that you remember scary events differently. Events that are frightening (and novel) seem to take up a larger chunk of our memory than they would based on time duration alone.

Published in both Latin and German, the 1474 Calendar, by Johannes Regiomontanus, includes three scientific instruments to measure time, including a lunar volvelle diagram with moving dials. Annotations in the volume show that it was referenced for close to thirty years and used as a family record to document the dates of birth and death of multiple children.

Image courtesy The Art Institute of Chicago.

Does time seem to pass more quickly to you than it used to? If you’re twenty-three right now, as you read this, then probably not. If you’re thirty-five, then maybe. If you’re sixty-five, then probably yes. That time seems to pass more quickly as we age is a bit of folk wisdom that happens to have been confirmed by empirical psychology. It’s not that short durations like a minute seem to pass more quickly for older people, but that time on longer scales like years or decades seems to fly by. Why would that be? One idea5 is that your brain is encoding new memories when you have a novel experience, not mundane experiences. Perception psychology shows that you’re likely to form more lasting memories in a week of adventure traveling in Vietnam than you are in an ordinary week of going to your job. So two years later, when you think back on your adventure travel week, it seems like it lasted longer than the week of routine you experienced right afterward (most of which you wouldn’t have committed to memory). A time period full of new experiences takes up more real estate in your memory, and so when you look back subjectively, it feels like time moved more slowly during that period.

When you’re very young, every week is like a week of adventure traveling, at least more so than when you’re older. Children are constantly experiencing new things. Some of these new things are really important (like their first crush) and some are totally unimportant (their first time tasting peanut butter Captain Crunch). But the point is that so many of their experiences are new, and it’s new experiences that get made into long-term memories. By middle age, on the other hand, life is generally pretty routine, and you’re not making as many memories. So of course time seems to speed up as you age – the fewer lasting memories you make per year, the more it will seem like those years went whizzing by.

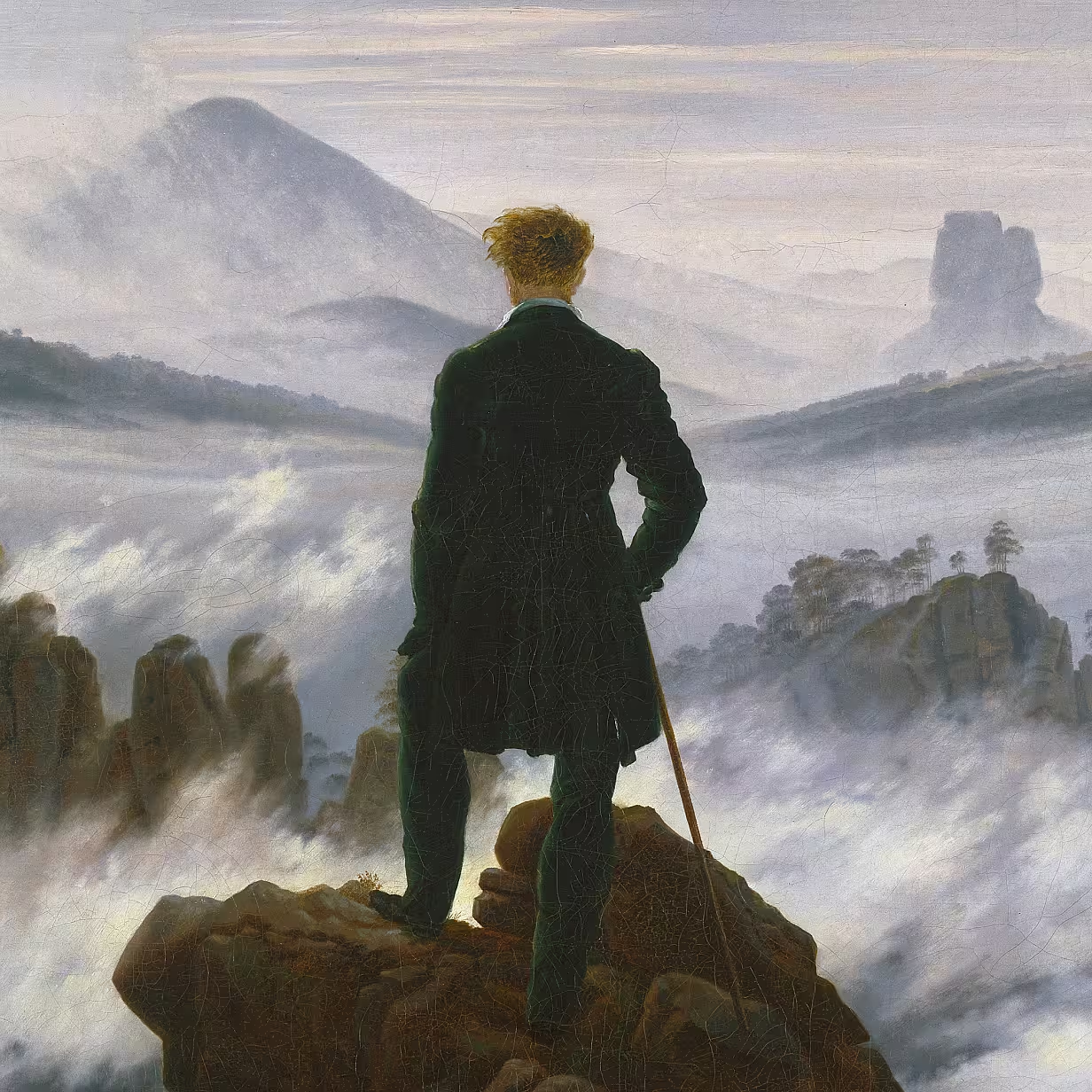

Utagawa Hiroshige, ca. 1833, woodblock print.

The peak of autumn, or the full moon on the eighth month of the lunar calendar, has always been important for East Asian poets.

The poem and image depict wild geese flying across the full moon.

こむな夜が 又も有うか 月に雁

Konna yo ga

mata mo arō ka

tsuki ni kari

Will there ever again

be such a marvelous night!

Wild geese against the moon.

Translation by John T. Carpenter

Image courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Can you imagine a situation where people all over the world might simultaneously experience a sensation of slowing time?

We’ve already lived through one such situation. Research shows that when the COVID-19 pandemic started and people across the globe were locked down, it was very common to feel like time dragged.6 This collective shift in time perception had a lot to do with emotion and motivation, as the situation created unique opportunities for negative feelings such as anxiety, stress, and boredom.

Interestingly, as we grew accustomed to being in lockdown, some people flipped to feeling like time flew by. These folks were more likely to report feeling relaxed and calm.

Reflect on periods in your life when time flew by compared to times when it dragged.

References

1 Dawson, Joe, and Scott Sleek. “The fluidity of time: Scientists uncover how emotions alter time perception”. Association for Psychological Science, 28 September 2018.

2 Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Innovation. Harper Perennial, 1997.

3 Tunnell, John. Zero Gravity Dallas Thrill Ride Amusement Park Promo. 2015.

4 Stetson et al. “Does time really slow down during a frightening event?”. PLOS One, 12 December 2007.

5 Dawson, Joe, and Scott Sleek. “Why does time seem to speed up with age”. Scientific American, 01 July 2016.

6 Droit-Volet S, Martinelli N, Chevalère J, Belletier C, Dezecache G, Gil S, Huguet P. “The Persistence of Slowed Time Experience During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Two Longitudinal Studies in France”. Frontiers in Psychology, 01 September 2021.

Make curiosity a daily ritual.

7 days free.

Sign up for more bites of curiosity in your inbox.

Ongoing discoveries, reflections, and app updates. Thoughtful ways to grow with us.

.svg)