The Perception of Time: Part I

Laws of physics work forward or backward—so why don’t we live in reverse? Discover how entropy sets direction.

Key Takeaways:

- Physics equations work forward and backward in time, but in reality, time only moves forward.

- The Second Law of Thermodynamics explains “time’s arrow”: entropy, or disorder, always increases.

- Entropy connects to memory formation, as creating memories releases heat and raises bodily entropy.

- The psychological arrow of time reflects entropy, explaining why we remember the past but not the future.

- Time travel remains impossible under current physics, since decreasing entropy to “reverse” memory or events defies thermodynamic laws.

Here’s a funny quirk about physics that you may not know: The equations describing the universe, the movements of the planets, the lifetime of a star – all those equations work equally well even if time started moving backward. From the astrophysicist’s perspective, the laws of the universe don’t care if reality is playing forwards or playing in reverse. Think of a song with no lyrics being played backwards – a C-sharp is still a C-sharp, and it’s still a whole tone below a D-sharp, even if the song is played in reverse.

Time is just the progression of events from the past to the future, but there are two kinds of time, at least in theory. Positive time is what we’re experiencing now, with the future coming after the past. Negative time is just the opposite, with our movie playing in reverse, and what we perceive to be the future coming before what we perceive to be the past. Of course, negative time is just a scientific hypothetical. The theories of Newton and Einstein and every other astrophysicist may hold true whether time moves forward or backwards - but as far as we know time never actually moves backwards. So… why not?

Time perception and why time moves forwards instead of backwards isn’t just conversation fodder for stoned college kids; it’s a legit scientific mystery. There isn’t a definitive answer, but there’s a plausible answer coming from a completely different area of physics, thermodynamics, that’s worth considering. Part of the Second Law of Thermodynamics, or the law of entropy, is that the entropy, or amount of disorder, in a system will increase rather than decrease.1 So, systems will tend to become more disordered, instead of spontaneously organizing. Sandcastles aren’t going to build themselves; they’re going to break down. You’ll notice that the idea of a trend moving from order to disorder implicitly contains a concept of time. The astrophysicist Sir Arthur Eddington put it this way:

Let us draw an arrow arbitrarily. If as we follow the arrow we find more and more of the random element in the state of the world, then the arrow is pointing towards the future; if the random element decreases the arrow points towards the past. That is the only distinction known to physics… I shall use the phrase 'time's arrow' to express this one-way property of time which has no analogue in space.” 2

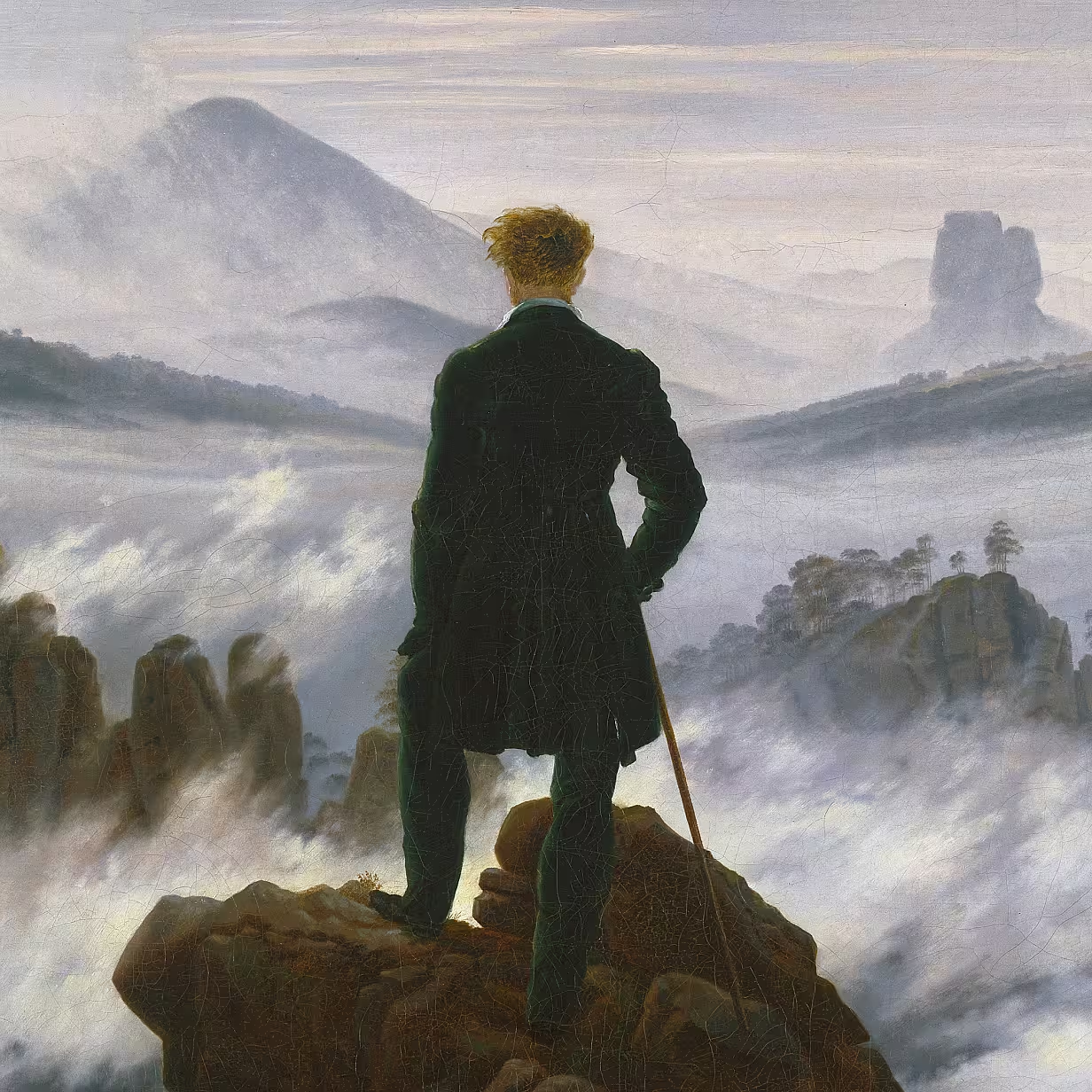

Image courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

If somebody asked you “Why can you remember the past but you can’t remember the future?,” would you be able to give them a good answer? This is actually another deep scientific question, this time about our minds instead of the universe itself. If “the arrow of time” refers to the one-way progression of time from past to future, the “psychological arrow of time” refers to our ability to have memories about the past but not the future. One possible reason (to be clear, a theoretical reason; none of this is beyond debate) why we remember the past instead of the future turns out to be very similar to the explanation above about why time moves forward instead of backwards.

The Second Law of Thermodynamics also entails that a hot object will lose its heat until it’s the same temperature as its surroundings. A hot cup of tea on the counter will never spontaneously get hotter (without us doing something to it); it will cool to match the temperature of the room. As it cools, it increases the entropy of the room, because having a bunch of heat contained in a small teacup is a kind of order. When that order is lost – as the tea cools – entropy can be said to increase. Entropy and heat are intimately related.

What’s any of that have to do with your memories? Well, when you make a memory, there are physical changes that have to happen to the neurons in your brain. Stephen Hawking postulated3 that these changes release (a tiny bit of) heat, as the cells do work to grow new connections. That heat is dissipated from our neurons to the rest of our body, just like the heat from the teacup is dissipated to the empty room. And just like the teacup cooling off increases the entropy of the room, forming the memory increases your entropy – because the heat is no longer contained in those memory-forming neurons, but is now dispersed through your body.

This is the psychological arrow of time. Your brain and body (or the brain/body of any organism that can remember things) forms a memory. The memory formation releases heat, which increases your entropy. And because entropy can only increase across time in a closed system (which we’ll call your body, for the sake of argument), your memories can only progress from past to future. To remember something in the future, you’d have to decrease your entropy, putting the heat those neurons formed when building a memory back into the neurons. The Laws of Thermodynamics teach us that this is impossible: For now, quantum physics time travel is not possible. Time is a one-way train, from past to future, from low entropy to high entropy, and there’s no way we can just hop off.

Eadweard Muybridge, 1880s, Photogravures.

Image courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

References

1 "What is the Second Law of Thermodynamics?," Live Science, 2022.

2 The Nature of the Physical World, Sir Arthur Eddington, 1928.

3 "Chapter 9: The Arrow of Time,” in A Brief History of Time, Stephen Hawking, 1988.

Build your practice of daily discovery.

7 days free.

Sign up for more bites of curiosity in your inbox.

Ongoing discoveries, reflections, and app updates. Thoughtful ways to grow with us.

.svg)