Mushroom Season: How Fungi Train Our Eyes

Learn how mushroom hunting rewires your brain to see.

Key Takeaways:

- Foraging draws on deep human instincts, blending risk, reward, and the thrill of discovery across countless mushroom species.

- Mushroom hunting trains perceptual learning, sharpening the brain’s ability to detect subtle patterns through practice and repetition.

- Selective attention develops over time, filtering out irrelevant details while attuning the eyes to cues that lead to successful finds.

- Novelty detection keeps curiosity alive, with unexpected fungi sparking dopamine, learning, and multisensory engagement.

- Simple everyday practices—like micro-looking, sketching, or naming one new thing—bring foragers’ attention skills into daily life.

Why are we so drawn to finding mushrooms?

Few activities combine peace and danger quite like foraging for mushrooms. It draws risk-takers and nature lovers, those seeking thrills and others mere tranquility.

Fanning out in parks and forests around the world, foragers quietly search the ground for fungi that range from delicious and harmless to disgusting and deadly. Even one misidentification can scar a forager for life. To be a good one thus requires attention, expertise, and patience.

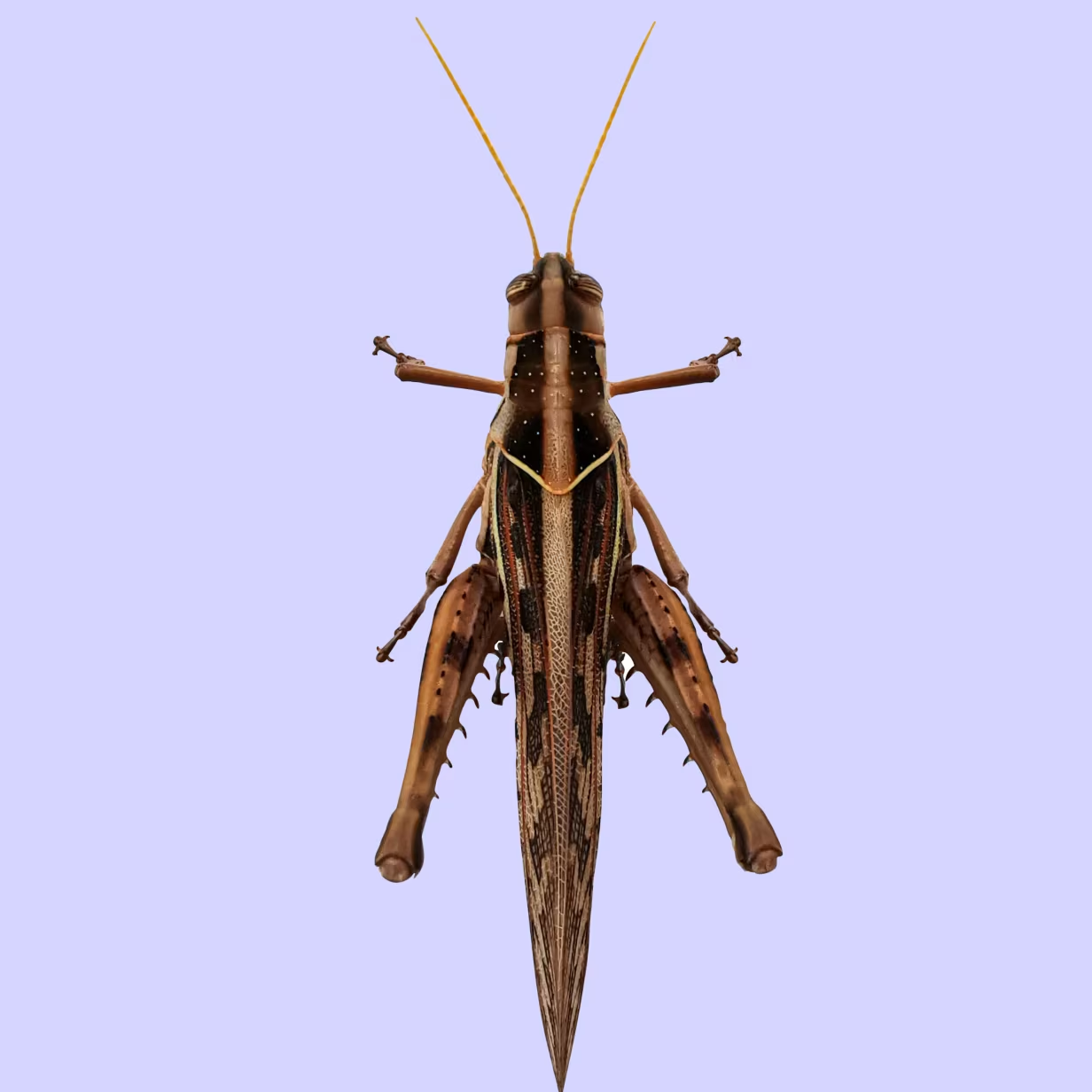

For those who possess these traits, there’s no end to the potential treasures unearthed during hunts. Thousands and thousands of mushroom species have been identified, and yet scientists estimate millions of fungi have yet to be named. Their distinct textures, smells, and forms mean even an experienced forager might discover something they’ve never seen before.

The mushrooms we do know about, from brainlike morels to trumpetesque chanterelles, can differ greatly or hardly at all. Spotting one, any one, on a dense forest floor is an accomplishment.

Yet the art of foraging is embedded deep within us, just waiting to be unearthed from our minds.

What happens cognitively when we learn to see fungi?

Born in 1829, Laura Bridgman was the first deaf-blind child to be formally educated. During infancy, a case of scarlet fever stole nearly all of her senses—after her illness, she couldn’t smell or taste, either. But in time, Bridgman developed a remarkable sense of touch. She could shake someone’s hand once and, after not seeing them for months, identify them merely by their grasp.

In his 1890 book The Principles of Psychology, renowned psychologist William James cites Bridgman’s incredible discernment as one example of humans’ astonishing capacity for sensory discrimination. With enough practice and savvy, people could figure out whether wine came from the top or bottom of a bottle just by taste or whether wheat was grown in Iowa or Tennessee, James adds.

The idea that “practice makes perfect” is fundamental to perceptual learning, or long-term shifts in perception brought on by experience. Over time, our brains get better at distinguishing between stimuli—sights, smells, tastes, sounds, and, as Bridgman proved, touches.

Perceptual learning is how people learn to forage. It’s also how they continue to improve over time.

Pattern recognition is one reason why. Over time, our brains get better at spotting subtle information or patterns (colors, shapes, and shadows) that match information we’ve observed in the past. In one study of hundreds of Finnish foragers, the majority derived their knowledge from their parents. Their families had passed down information about mushrooms that gave them intuitive pattern recognition. They could find the best places to forage and pick mushrooms based on instinct without being able to explain all of their characteristics with certainty.

To tolerate this ambiguity, foragers do use heuristics, or simple strategies and rules, to take comfort in their finds. For example, they often avoid white mushrooms because there’s a chance one could be an Amanita virosa, a highly poisonous mushroom also known as the “destroying angel.”

In time, experienced foragers notice that their eyes have been trained to filter out what they don’t expect to see, focusing on features of the environment that are most likely to result in a discovery. As one respondent in the study describes this selective attention, “I have hunted mushrooms since I was a child, and my eye has been calibrated to mainly notice the few edible and beautiful or interesting mushrooms. Others I do not see.”

How does mushroom hunting cultivate attention and curiosity?

While experienced foragers learn how to scan the forest floor to identify mushrooms they expect to see, they don’t gloss over potential discoveries. Essentially, the mind has created a model of what it anticipates sensing based on memory, and any disruption to that prediction may either be a threat or an opportunity for more feel-good chemicals in the brain to flow. This is known as novelty detection, when unfamiliar stimuli heighten dopamine and learning.

Mushrooms are full of novelty. They frequently defy expectations, growing in unexpected places, changing form quickly, and often appearing right after rain. This unpredictability, along with the vast array of species found around the world, sustains our curiosity. And the manifestation of this curiosity, through close examination, crouching, and touching, involves multiple senses, the integration of which has been shown to reduce stress and promote psychological well-being.

How can we bring this kind of seeing into everyday life?

You don’t have to leave your “mycological mindset” in the forest. Here are a few ways to use it in your everyday life:

- Practice micro-looking: Take 5 minutes to study one small patch of ground or sidewalk crack. What do you notice?

- Repeat a route to practice novelty detection: Walk the same path daily. What changes do you perceive from day to day? What didn’t you anticipate?

- Sketch what you see: Drawing unfamiliar forms enhances memory and slows perception.

- Name one new thing: Each day, identify one object, texture, or pattern you had never focused on before. How did your understanding of it shift?

Mushrooms aren’t just a quirky fixation. Foraging trains us to look. And when you do slow to see what’s around you, you’ll never be bored again.

References

Cavanagh, Bliss, et al. “Changes in Emotions and Perceived Stress Following Time Spent in an Artistically Designed Multisensory Environment,” Medical Humanities, vol. 47, no. 4, 2021, mh.bmj.com/content/47/4/e13.

James, William. The Principles of Psychology. Henry Holt and Company, 1890.

Kaaronen, Rauli O. “Mycological Rationality: Heuristics, Perception and Decision-Making in Mushroom Foraging,” Judgment and Decision Making, vol. 15, no. 5, 2020, www.cambridge.org/core/journals/judgment-and-decision-making/article/mycological-rationality-heuristics-perception-and-decisionmaking-in-mushroom-foraging/E3B5C14DE7FADACB68AFD4C8029A233C.

Tiitinen, H., et al. “Attentive Novelty Detection in Humans Is Governed by Pre-Attentive Sensory Memory,” Nature, vol. 372, 1994. doi.org/10.1038/372090a0.

Make curiosity a daily ritual.

7 days free.

Sign up for more bites of curiosity in your inbox.

Ongoing discoveries, reflections, and app updates. Thoughtful ways to grow with us.

.svg)