The Hidden Architecture of Resilience

How awe, survival, and nature’s quiet genius reshape what we think we know about resilience.

Key Takeaways:

- Resilience is a system, not a single trait. Psychologist Ann Masten calls it “ordinary magic”—a collection of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral processes that grow over time.

- Emotional flexibility builds resilience. Research shows that resilient people recover from stress more quickly, often using humor, awe, or perspective shifts to adapt.

- Nature models resilience through intelligent adaptation. Desert plants like cacti and creosote bushes thrive by conserving energy, knowing when to grow, and coexisting with their environments.

- Resilience is often collective, not individual. The revival of Japan’s Genji fireflies demonstrates how small acts of generosity and community care can restore balance and strength over time.

- Building resilience in daily life starts with awareness. Practicing awe, tracking grounding habits, conserving energy like the cactus, and protecting moments of beauty all strengthen our capacity to endure and adapt.

What is resilience, really?

Adversity often arrives in an instant. A layoff, a crash, an illness. Our response to these events might seem like it arises just as quickly and, sometimes, out of nowhere. How else could we explain the behavior of Aron Ralston, who famously cut off his arm after it got pinned beneath a boulder in Utah for five days, then hiked seven miles to safety? Or Juliane Koepcke, the lone survivor of a two-mile fall from a plane into the Peruvian rainforest, where she survived for more than 10 days on her own before being rescued?

But resilience—the ability to bounce back, to push through—doesn’t normally manifest as suddenly as a life-or-death adrenaline rush. Researchers have instead found that it builds over time. According to psychologist Ann Masten, resilience is “ordinary magic”—a set of cognitive and behavioral processes that, under ideal circumstances, we develop gradually. That way, when a challenge does suddenly present itself, we’re prepared to disarm the threat with inner and external tools. This doesn’t happen all at once, though; stress will still affect us. But we don’t need superhuman strength or resolve to navigate difficult situations. Oftentimes, we can just lean on what our brains and bodies are telling us and adapt accordingly.

Positive psychology research expands on this idea. A 2004 study by Barbara L. Fredrickson and Michele M. Tugade found that resilient people tend to show greater emotional flexibility and maintain higher levels of positive emotion during adversity. Some even use humor to help defuse a situation. This doesn’t mean they avoid difficulty, but rather that they access a broader emotional range to navigate it. Their cardiovascular reactions to stressors return to normal more quickly than those of their less-resilient peers, the study found.

Even brief experiences of awe—the feeling of being in the presence of something vast and beyond immediate understanding—can contribute to resilience. Research has shown that people who experienced awe reported feeling they had more time, a greater willingness to help others, and less stress. Awe stretches perspective, creating space to reframe our challenges.

Resilience, then, is not a single trait but a system. It is how we metabolize difficulty and subtly adapt. And like all living systems, it often hides its intelligence in plain sight.

How do desert plants model intelligent survival?

Gaze across a desert dotted with cacti, and everything seems pretty still. But beneath the surface of these plants, little revolutions are underway.

Thriving in the world’s harshest landscapes, cacti must constantly adapt to survive. Generally speaking, they use a specialized form of photosynthesis called crassulacean acid metabolism, or CAM, that allows them to gather carbon dioxide at night and store it for use during the day. This minimizes water loss—a quiet, ingenious form of conservation.

Individual species of cacti evolve in their own ways. Take the saguaro cactus, which is native to the Sonoran Desert in Arizona. While rain is a rare event in this part of the world, this cactus absorbs every last drop, storing water in its grooved walls and expanding ever so slightly. In the scorching heat, it’s careful to use its reserves gradually. Its flowers are mindful of the high temperatures, too; they only open at night and, over the course of the year, subtly shift positions to the shadier side of the plant to avoid the sun.

Then there's the prickly pear cactus, which balances resilience and generosity. It uses thick pads to store water, spines to deter predators, and bright flowers to attract pollinators. The pads are edible and provide moisture and nutrients to desert animals and humans alike. It protects itself, but it also nourishes others.

Beyond cacti, other desert plants offer powerful models of adaptation. The creosote bush, for instance, thrives in the Mojave and Sonoran deserts by entering dormancy during extreme drought, essentially pausing its growth until rain returns. Its roots can extend up to 60 feet to find water, and some colonies are believed to be among the oldest living organisms on Earth. Creosote's strategy isn’t to push forward no matter what—it’s to wait wisely and act when conditions are right.

These adaptations form an architecture of resilience: a structure built not to resist the environment, but to coexist with it.

They also offer a key insight: Resilience isn’t about powering through. It’s about knowing when to conserve, when to offer, and how to survive together in even the toughest conditions.

As we admire the hidden resolve of these cacti, we can ask ourselves: What are our pleated walls? What inner structures have we built to store strength, regulate energy, and protect what matters most?

What do fireflies reveal about external resilience?

Over a century ago, Genji fireflies were famous in Moriyama, Japan. Brilliant displays lit up the countryside. Tourists traveled en masse to see them. Yet these lightning bugs became so coveted that they nearly vanished from this part of the world altogether. Hunters were snagging females and their eggs by the thousands every night. Even the most adaptable insect couldn’t keep up with that rate of capture.

In the 1920s, the generosity of one man helped restore this population. Kiichiro Minami gathered his own firefly larvae by wading through a river. But instead of selling them, he raised them in pottery vases, feeding them a kind of river snail called kawanina. He then provided moist soil and moss for these larvae to grow into adults and lay eggs. Over time, he released them back into the wild.

His generosity was contagious; others performed the same firefly rescues and restoration. Cities cleaned up their rivers for them to thrive.

Decades later, the Moriyama Firefly Festival, or Hotaru Matsuri, is now a celebration of this population’s resilience. But the Genji firefly couldn’t have done it alone. It was the efforts of a broad community that helped replenish this species very gradually over time. It required lots of small, simple acts tucked between the demands of a day.

The survival of this firefly shows us that resilience doesn’t have to be a solo act. Nor does it necessarily create change overnight. Small measures can add up to major shifts over time.

How can we build more resilience into everyday life?

Resilience isn’t something you have or don’t have. It’s something you build over time, often in quiet moments. Here are a few research-informed ways to strengthen it:

- Practice perspective shifts. Awe helps us zoom out. Whether it’s stargazing, looking at old trees, or noticing a child’s curiosity, these moments reset our sense of scale.

- Track your strategies. Notice the habits or choices that help you stay grounded—whether it's journaling, walking, setting boundaries, or asking for help. These are your roots and ribs.

- Reflect like a cactus. What strategies help you hold onto energy, especially in difficult seasons? Where have you chosen flexibility over force?

- Protect what glows. The firefly’s message is simple: Beauty matters, even when it’s brief. What small joys can you notice, celebrate, or help preserve?

References

Fredrickson, Barbara L., and Michele M. Tugade. “Resilient Individuals Use Positive Emotions to Bounce Back from Negative Emotional Experiences.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 86, no. 2, 2004, psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2F0022-3514.86.2.320.

Lewis, Sara. “For the Sake of Their Glow.” Undark, 1 June 2017, undark.org/2017/06/01/sake-their-glow-moriyama-japan-fireflies/.

Masten, Ann S. “Ordinary Magic: Resilience Processes in Development.” American Psychologist, vol. 56, no. 3, 2001, ocfcpacourts.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Ordinary_Magic_Resilience_Process_000935.pdf.

Piff, Paul K., et al. “Awe, the Small Self, and Prosocial Behavior.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 108, no. 6, 2015, www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/psp-pspi0000018.pdf.

Pleitgen, Frederik. “Survivor Still Haunted by 1971 Air Crash.” CNN, 2 July 2009, www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/europe/07/02/germany.aircrash.survivor/.

Posada-Swafford, Angela. “The Surprising Tricks Cacti Use to Survive the Harshest Climates on Earth.” National Geographic, 22 Oct. 2024, www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/cactus-resilient-scientists-climate-change.

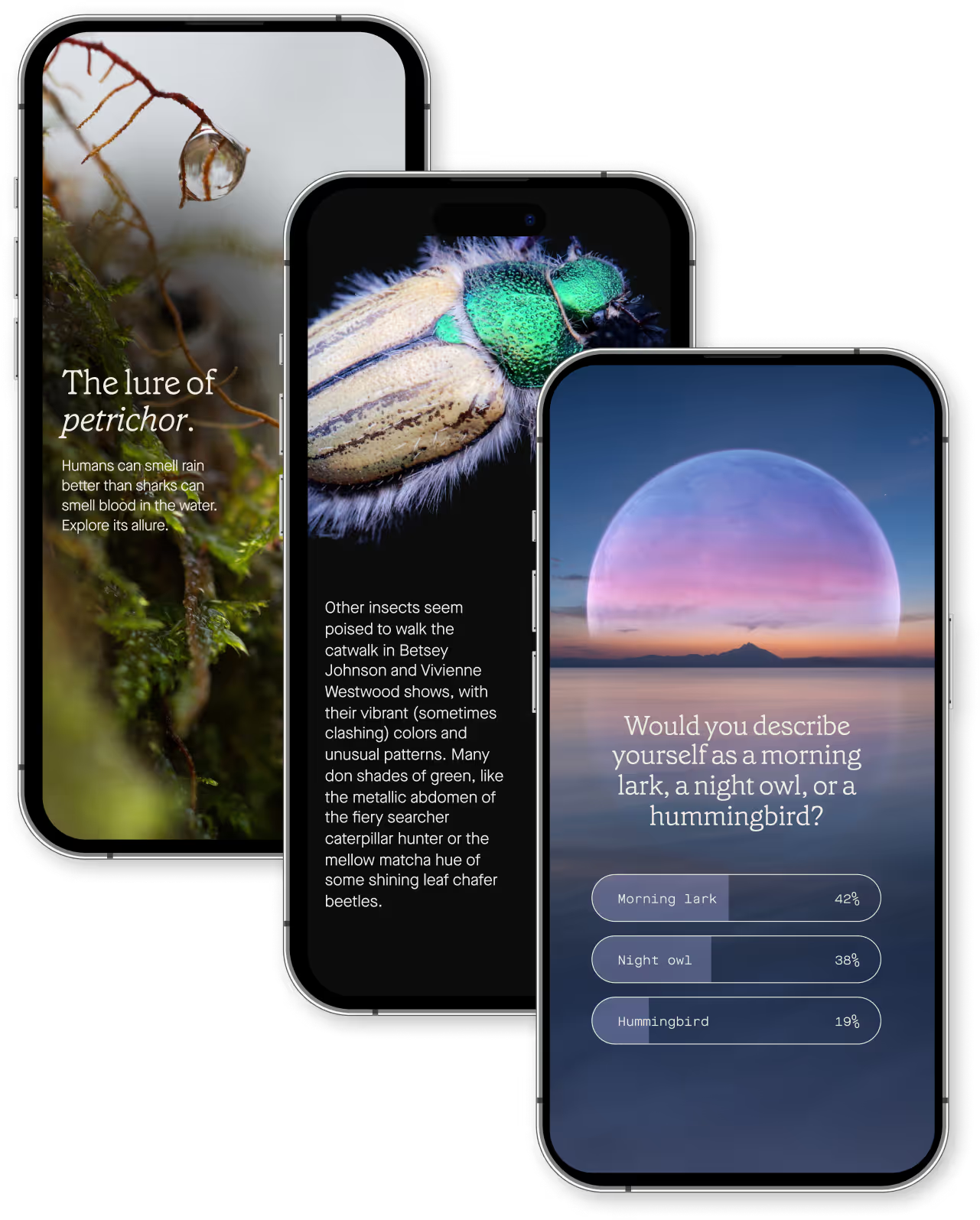

Build your practice of daily discovery.

7 days free.

Sign up for more bites of curiosity in your inbox.

Ongoing discoveries, reflections, and app updates. Thoughtful ways to grow with us.

.svg)